Internal Solitary Waves

Overview of Internal Solitary Waves

Density interfaces between two fluids are able to support the propagation of waves. Just like the interface between air and water supports the waves we’re used to seeing at the beach, internal waves can form on interfaces within the ocean, produced by vertical variations in temperature and salinity (and in turn, density). These waves are a crucial mechanism in the global cascade of energy from large scale inputs (tides and wind), to molecular scale output.

Internal Solitary Waves are a particular kind of these waves, where a balance of nonlinear steepening and wave dispersion produce waves with large amplitude. Similar to the Surface Solitary Waves first discovered by John Scott Russell, these internal solitary waves are able to travel large distances without significant change of form or magnitude, and do not interact when they come together.

Below is a summary of my research into internal solitary waves and the methods I used to do so.

Laboratory Methods

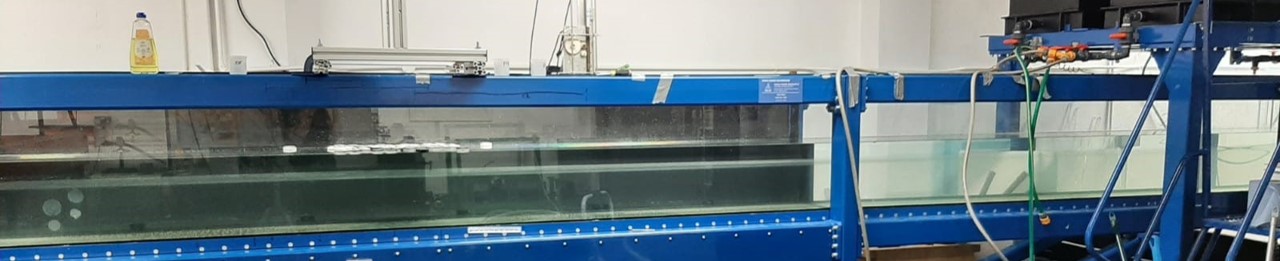

As studying internal waves in situ, particularly in the Arctic Ocean, is practically challenging, I study internal waves in the laboratory using a purpose built 7m long, 30cm deep flume at Newcastle University. The tank is initially filled with dense, salty water, before a layer of fresher (lighter) water is slowly added to the surface using an array of sponges to prevent mixing with the lower layer. At one end of the tank is a removable gate, and behind this a further volume of the lighter fluid is added to the surface, to produce a step in the pycnocline. On removal of the gate, an internal wave forms, and propagates along the tank:

We visualise the flow using seeding particles illuminated by a vertical thin light sheet, and use Particle Image Velocimetry in DigiFlow to calculate synoptic velocity and vorticity fields. This method allows us to gain high spatial and temporal resolution to our observations, and really pick apart any dynamics we observe.

As part of the laboratory experiments, I wrote a MATLAB package for the processing of DigiFlow and other laboratory data: Laboratory Code

Numerical Methods

In addition to the laboratory, we use the pseudo-spectral Navier-Stokes solver, SPINS (available here) to extend our experimental output further, and to gain a full suite of simultaneous measurements not available in the laboratory. The model was developed at the University of Waterloo by (Subrich et al., 2013), and as part of my project I spent a 6 week research placement in Waterloo to carry out further work with SPINS to produce a new diagnostic tool for understanding mixing in numerical models of stratified flows, which can be found via GitHub.

As part of the numerical work, I built on previous work to improve offline analysis of mixing and energetics, which can be found and documented at two GitHub repositories: SPINS_energetics SPINS_USP

Shoaling Internal Solitary Waves

As the first part of my PhD, recently published in Journal of Fluid Mechanics, I investigated the effects of varying stratification type on the way in which internal solitary waves break when propagating over a smooth, linear slope. Previous work had identified a classification system analogue to the wave breaking classifications of surface waves, but our work identified that some dynamics could be suppressed in other stratification types, depending on the location of the vertical density gradient relative to the dynamics. This altered the previous classification diagram based on wave steepness, and topographic slope, and added another consideration of stratification. This work is summarised in this video:

A further paper, published in Environmental Fluid Mechanics investigates further the problem of varying stratifications on shoaling internal solitary waves, but focussing on slope angles that better represent the real-world ocean. In this scenario, ISWs of depression give wave to a series (train) of ISWs of elevation, or pulses, which can commonly be observed as cold pulses. Such “cold pulses” are well documented as a potential mechanism for improving survival of benthic ecosystems suffering from heat stress under a changing climate, and as such are an important mechanism for us to study further. In our paper, we investigated the transport of these pulses of fluid upslope, and identified a new process of pulse formation in the broadest stratification centred on the centre of the tank.

Below is an interactive summary figure of the paper, it shows how the breaker type (F=Fission, S = Surging, P = Plunging, C = Collapsing, IS = Surger with KH instability), depends upon internal wave steepness ( Aw / Lw ) and slope (s). Click on any of the labelled points to see the corresponding video of that wave:

Internal Waves in Ice Covered Waters

In the Arctic Ocean, these waves are much less energetic, but are particularly important in driving the circulation and distribution of water masses. With declines of sea ice, understanding how internal waves interact with sea ice, and how sea ice affects them is required to understand the Arctic’s future. Observing waves in situ is particularly difficult so my project uses laboratory experiments to investigate the interactions between sea ice and internal waves. Using floats to model sea ice, we visualise the float motion from above, alongside visualising the wave:

To analyse the motion of floats, we built a float motion model, which can be found here: ISW Float Motion Model