ISWs and Sea Ice

The Arctic Ocean is a unique oceanographic environment for a few key reasons:

- Unlike most oceans around the world, the Arctic Ocean’s heat is contained at intermediate depth, as warm but salty waters are overlaid by cold but fresh waters. The heat remaining at depth is crucial for the presence of sea ice.

- Internal Tides are unable to propagate freely at high latitudes, their nonlinear counterparts become particularly important

- The presence of sea ice changes the transfers of heat and momentum between the ocean and atmosphere, including the generation and propagation of internal waves. Yet, this sea ice is rapidly declining, and a key question for us is what those changes will do to the Arctic Ocean.

For these reasons, understanding the processes around internal waves and ice are important. Observing this region directly is difficult and expensive, remote sensing provides us with some insight, but we use idealised experiments to understand the processes better. Carr et al. (2019) conducted experiments with real ice interacting with Internal Solitary Waves (published in Geophysical Research Letters). These have been followed up by further experiments, currently under review.

The Motion of Sea Ice under the influence of Internal Solitary Waves

Floating bodies representing ice move under the influence of internal solitary waves.

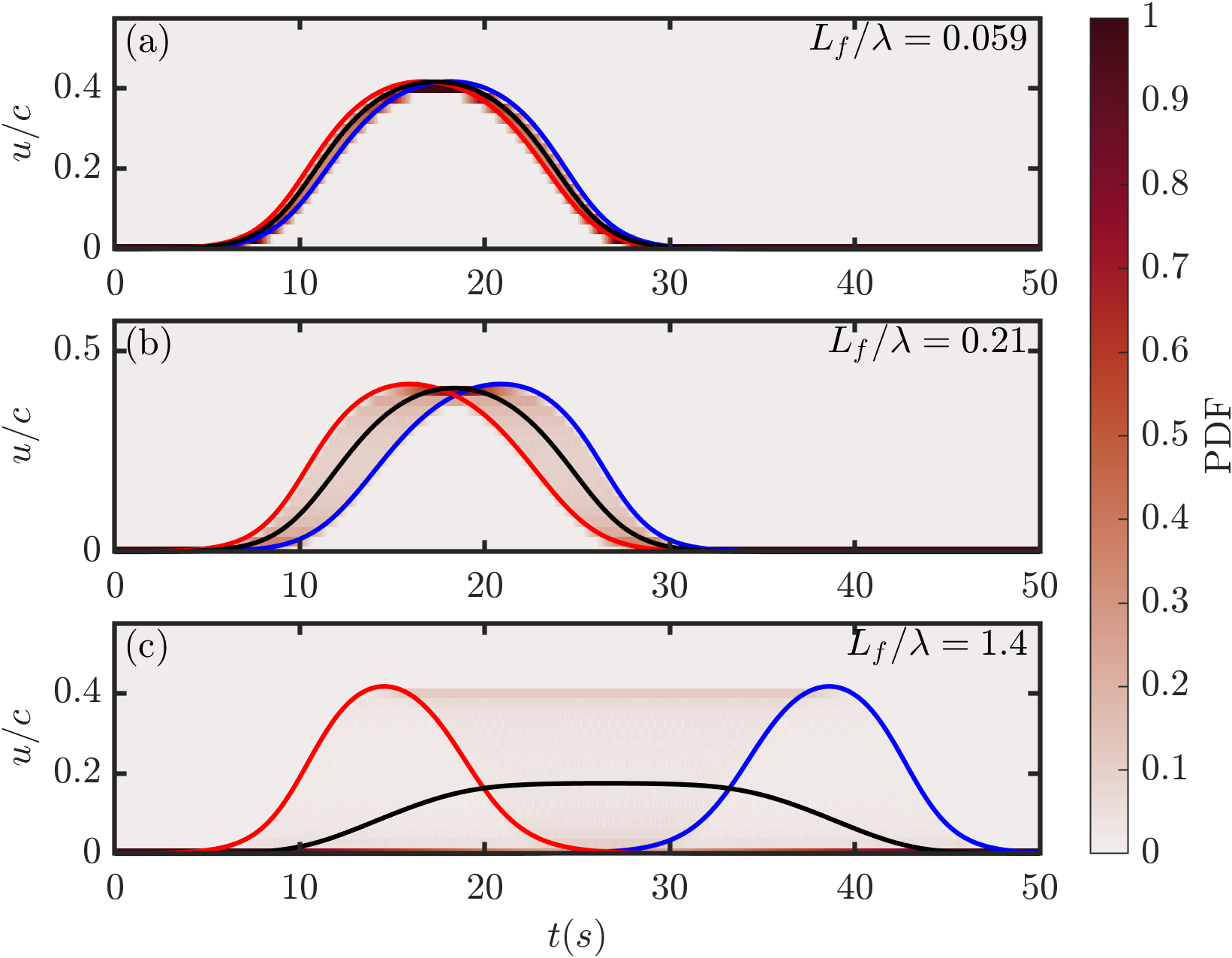

For a given wave, the larger the float, the slower the float moves, and for a given float, the larger the wave the faster the float moves. The intuitive explaination for this is the relative masses (and therefore inertia) of the float, however it turns out this has more to do with the waveform. Either side of a wave is still water, and when a float is much longer than a wavelength, the majority of the float is influenced by the still water, so it’s velocity decreases.

Flow interactions

Depending on ice and wave properties, a variety of deformation of the wave-induced flow by the ice have been identified:

- When the ice is small in comparison to the wave, there is minimal flow disruption, as the floats propagate at a speed very similar to the wave-induced flow.

- Larger ice floes where the edge of the ice does not directly interact with the ice edge produces a pair of vortices at each end of the floe.

Both features can be described in the same way using the flow relative to the float speed

-

Where the underside of the ice is rough, the dissipation of Turbulent Kinetic Energy under the ice were comparable to that at the pycnocline (and therefore considerably enhanced from a no-ice case).

-

Thick ice (where the pycnocline directly interacts with the ice edge) causes significant deformation of the wave shape. For a small wave, the wave was effectively destroyed, whilst for a larger wave, the wave showed overturning features associated with a Kelvin-Helmholtz instability.